Фармакогнозия

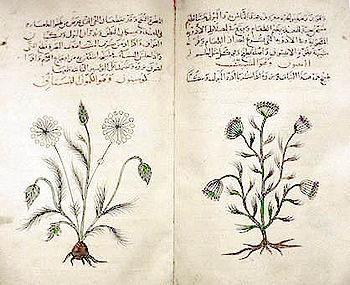

Фармакогнозия (от др.-греч. φάρμακον — лекарство и γνῶσις — познание) — одна из фармацевтических наук, изучающая лекарственные средства, получаемые из лекарственного растительного и животного сырья, продуктов жизнедеятельности растений и животных, а также некоторые продукты их первичной переработки (эфирные и жирные масла, смолы, млечные соки и др.)

Задачи фармакогнозииПравить

- Изучение лекарственных растений, как источников фармакологически активных веществ. Изучают морфологические признаки растений, географию их обитания, химический состав (фитохимия), способы и сроки заготовки сырья, фармакологическое действие веществ, способы и сроки хранения ЛРС.

- Ресурсно-товароведческие исследования лекарственных растений. Выявление их мест произрастаний в дикой природе. Определение зарослей, потенциальных запасов, ежегодных объёмов заготовки.

- Нормирование и стандартизация лекарственного растительного сырья, разработка проектов нормативно-технических документов (НТД), проведение анализа ЛРС и разработка новых методов стандартизации ЛРС.

- Изыскание новых лекарственных средств растительного происхождения с целью расширения ассортимента и создания более эффективных лекарств.

- существует зоофармакогнозия — это методы лечения растительными и не обязательно съедобными веществами, «подсмотренные» у животных.

Фармакогнозия использует методы органической и аналитической химии, а также ботаники.

ИсторияПравить

ЛитератураПравить

- Гаммерман А. Ф., Курс фармакогнозии, 6 изд., Л., 1967;

- Dragendorf G., Die Heilpflanzen der verschiedenen Volker und Zeiten, Stuttg., 1898;

- Handbuch der Pharmakognosie, 2 Aufl., hrsg. A. Tschirch, Bd 1-3, Lpz., 1930-33.

См. такжеПравить

Внешние ссылкиПравить

- Фармакогноз — Фармакогноз — посланник фармакогнозии

- American Society of Pharmacognosy

- GA/Society for Medicinal Plant Research

- ESCOP-European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy

- International Society for Ethnopharmacology

- American Botanical Council

- Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine

- Centre for Pharmacognosy and Phytotherapy, School of Pharmacy, University of London

ПримечанияПравить

]</ref>

The farming of plant or animal species, used for medicinal purposes has caused difficulties. Rob Parry Jones and Amanda Vincent write:

- One solution is to farm medicinal animals and plants. Chinese officials have promoted this as a way of guaranteeing supplies as well as protecting endangered species. And there have been some successes—notably with plant species, such as American ginseng—which is used as a general tonic and for chronic coughs. Red deer, too, have for centuries been farmed for their antlers, which are used to treat impotence and general fatigue. But growing your own is not a universal panacea. Some plants grow so slowly that cultivation in not economically viable. Animals such as musk deer may be difficult to farm, and so generate little profit. Seahorses are difficult to feed and plagued by disease in captivity. Other species cannot be cultivated at all. Even when it works, farming usually fails to match the scale of demand. Overall, cultivated TCM plants in China supply less than 20 per cent of the required 1.6 million tonnes per annum. Similarly, China's demand for animal products such as musk and pangolin scales far exceeds supply from captive-bred sources.

- Farming alone can never resolve conservation concerns, as government authorities and those who use Chinese medicine realise. For a start, consumers often prefer ingredients taken from the wild, believing them to be more potent. This is reflected in the price, with wild oriental ginseng fetching up to 32 times as much as cultivated plants. Then there are welfare concerns. Bear farming in China is particularly controversial. Around 7600 captive bears have their bile "milked" through tubes inserted into their gall bladders. The World Society for the Protection of Animals states that bear farming is surrounded by "appalling levels of cruelty and neglect".[1] Chinese officials state that 10 000 wild bears would need to be killed each year to produce as much bile, making bear farming the more desirable option. The World society for the Protection of Animals, however, states that "it is commonly believed in China that the bile from a wild bear is the most potent, and so farming bears for their bile cannot replace the demand for the product extracted from wild animals".

- One alternative to farming involves replacing medical ingredients from threatened species with manufactured chemical compounds. In general, this sort of substitution is difficult to achieve because the active ingredient is often not known. In addition, most TCM users believe that TCM compounds may act synergistically so several ingredients may interact to give the required effect. Thus TCM users often people prefer the wild source. Tauro ursodeoxycholic acid, the active ingredient of bear bile, can be synthesised and is used by some Western doctors to treat gallstones, but many TCM consumers reject it as being inferior to the natural substance from wild animals.[2]

Acceptance in the United StatesПравить

In the US pharmacognosy has been long lumped together with quack herbalism by both proponents and opponents. Traditional herbalism is regarded as a method of alternative medicine and considered suspect since the Flexner Report of 1910 led to the closing of the eclectic medical schools where botanical medicine was exclusively practiced.

This situation is further complicated by most pharmacognostic studies in the latter part of the 20th Century having been published in languages other than English such as German, Dutch, Chinese, Japanese, Korean and Persian. Some of the important botanicals have been incorporated into the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) determinations of drug safety. In 1994, US Congress passed the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA), regulating labeling and sales of herbs and other supplements. Most of the 2000 US companies making herbal or natural products[3] choose to market their products as food supplements that do not require substantial testing and give no assurance of safety and effectivity. te:ఔషధశాస్త్రం -->

- ↑ The Trade in Bear Bile: Courtesy of World Society for the Protection of Animals

- ↑ Ошибка цитирования Неверный тег

<ref>; для сносокautogenerated1не указан текст - ↑ Whole Foods Magazine